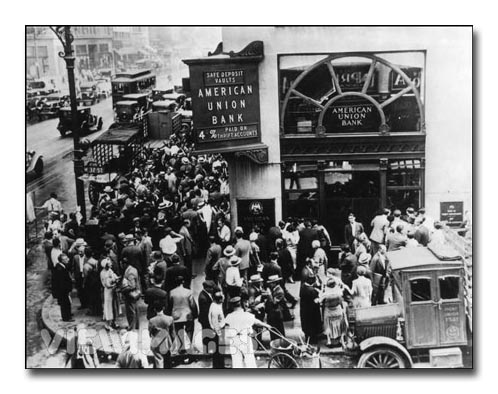

Iceland took serious objection to similar banker duplicity and jailed over 20 banking executives for their role in acts of fraud and the impact on its economy. We should be doing the same in the United States too – but are extremely far off from even contemplating such a move. But Fleischmann is a threat to the cover-up: she knows exactly how the Chase fraud was carried out and wants desperately to spill the beans and tell the whole story. Although doing this will probably destroy her future career and may cost her every penny she has, she’s still more than willing.

Six years after the crisis that cratered the global economy, it’s not exactly news that the country’s biggest banks stole on a grand scale. That’s why the more important part of Fleischmann’s story is in the pains Chase and the Justice Department took to silence her.

She was blocked at every turn: by asleep-on-the-job regulators like the Securities and Exchange Commission, by a court system that allowed Chase to use its billions to bury her evidence, and, finally, by officials like outgoing Attorney General Eric Holder, the chief architect of the crazily elaborate government policy of surrender, secrecy and cover-up. “Every time I had a chance to talk, something always got in the way,” Fleischmann says.

Alayne decided to step forward with the truth after watching Holder whitewash his actions in the “No Company Is Too Big to Jail” video, in which Holder made it clear that he had no intention of criminally prosecuting any of the finance industry execs who had done horrible things to America’s economy.

“I tried to go on with the things I was doing, but I just stopped sleeping and couldn’t eat,” she says. “It felt like I was trying to keep this secret and my body was literally rejecting it.”

Alayne was approached this summer by a new investigation team:

…she still has reason to be deeply worried that nothing will be done. Even if the investigators build strong cases against executives who oversaw Chase’s fraud, Holder or whoever succeeds him can still make the whole thing disappear by negotiating a soft landing for the company. “That’s the thing I’m worried about,” she says. “That they make the whole thing disappear. If they do that, the truth will never come out.”

In September, at a speech at NYU, Holder defended the lack of prosecutions of top executives on the grounds that, in the corporate context, sometimes bad things just happen without actual people being responsible. “Responsibility remains so diffuse, and top executives so insulated,” Holder said, “that any misconduct could again be considered more a symptom of the institution’s culture than a result of the willful actions of any single individual.”

In other words, people don’t commit crimes, corporate culture commits crimes! It’s probably fortunate that Holder is quitting before he has time to apply the same logic to Mafia or terrorism cases.

Fleischmann, for her part, had begun to find the whole situation almost funny.

“I thought, ‘I swear, Eric Holder is gas-lighting me,’?” she says.

Ask her where the crime was, and Fleischmann will point out exactly how her bosses at JPMorgan Chase committed criminal fraud: It’s right there in the documents; just hand her a highlighter and some Post-it notes – “We lawyers love flags” – and you will not find a more enthusiastic tour guide through a gazillion-page prospectus than Alayne Fleischmann.

She believes the proof is easily there for all the elements of the crime as defined by federal law – the bank made material misrepresentations, it made material omissions, and it did so willfully and with specific intent, consciously ignoring warnings from inside the firm and out.

She’d like to see something done about it, emphasizing that there still is time. The statute of limitations for wire fraud, for instance, has not run out, and she strongly believes there’s a case there, against the bank’s executives. She has no financial interest in any of this, no motive other than wanting the truth out. But more than anything, she wants it to be over.

In today’s America, someone like Fleischmann – an honest person caught for a little while in the wrong place at the wrong time – has to be willing to live through an epic ordeal just to get to the point of being able to open her mouth and tell a truth or two. And when she finally gets there, she still has to risk everything to take that last step. “The assumption they make is that I won’t blow up my life to do it,” Fleischmann says. “But they’re wrong about that.”