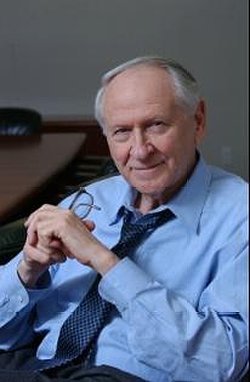

I missed marking the passing of William Safire, who authored my favorite newspaper column On Language until he became late in 2009 at the age of 79. So let me celebrate his work and how it touched me me, a little bit, now.

I missed marking the passing of William Safire, who authored my favorite newspaper column On Language until he became late in 2009 at the age of 79. So let me celebrate his work and how it touched me me, a little bit, now.

Safire inspired my love for language to blossom into good and accurate writing and introduced me to etymology – the topic of his twice weekly New York Times Magazine column for over 30 years. Teen me didn’t know that there was such a thing as etymology. It’s the study of words, and it’s fascinating. Safire’s compelling writing style pulled me right in. Google offers this definition:

Etymology noun

the study of the origin of words and the way in which their meanings have changed throughout history.

I learned from Safire that because of their history and the meaning they were coined to convey, there is a right way to quote proverbs – and how they’re quoted totally matters (as does punctuation). For example:

“As for the negative consequences of eliminating industrial society – well, you can’t eat your cake and have it too – to gain one thing you have to sacrifice another.” In a letter discovered in Kaczynski’s mother’s home – a letter that inexplicably found its way into the media – the same proverb appears in the same words, with the same lack of a comma before the “too.”

In both instances, the having and the eating were in correct order. Many people err in saying, “You can’t have your cake and eat it, too,” because you can – first you have it, and then you eat it. The impossible is the other way around; to “eat your cake and have it” is the absurdity that makes the point.

http://www.nytimes.com/1996/06/02/magazine/on-language-two-b-s-in-a-bomber.html

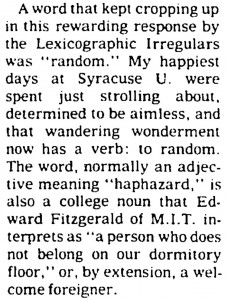

Because his columns are both archived and often quoted, Safire can still help me out. I wanted to know his thoughts on the word ‘random’, which my sons use in a context that matches neither its origins or the meaning I was taught as a girl, and Safire did not disappoint. The Online Etymology Dictionary gives the traditional meaning along with Safire’s 1980 commentary on how the word has slipped into a slightly different context:

“having no definite aim or purpose,” 1650s, from at random (1560s), “at great speed” (thus, “carelessly, haphazardly”), alteration of Middle English noun randon “impetuosity, speed” (c. 1300), from Old French randon “rush, disorder, force, impetuosity,” from randir “to run fast,” from Frankish *rant “a running” or some other Germanic source, from Proto-Germanic *randa (cognates: Old High German rennen “to run,” Old English rinnan “to flow, to run;” see run (v.)).

In 1980s U.S. college student slang it began to acquire a sense of “inferior, undesirable.” (A 1980 William Safire column describes it as a college slang noun meaning “person who does not belong on our dormitory floor.”) Random access in reference to computer memory is recorded from 1953. Related: Randomly; randomness.

Safire’s documentation about ways modern youth are using this word appears in 2 pages of Google results. Safire also discussed ‘random’ in a 1988 column entitled Youthspeak:

More than any other group, it would seem, students constantly use words in entirely new ways. Take random. When something makes no sense and you are resigned to its utter nonsensicalness, ”it is random, really random, totally random.” ”This really random guy” would not be a flattering way of describing a new acquaintance. And radical is no longer the make-the-world-over-in-our-own-image word used ad nauseam during the 60’s. Radical – often shortened to rad – means great, wonderful, remarkable.

William Safire was also a bestselling book writer. His take on language radically affected me, and I’m awfully grateful for its influence. Thank you, Good Sir. Rest in peace and harmony.